It’s Masters week! Albeit seven months later than we imagined, but we’re finally here for the greatest tournament in golf.

Since 1945, no masters competition has been played later than 15th April.

So what will be different this time around?

On first appearances, it’s the same old Augusta but with an autumnal twist. The classic pearl white pockets of sand litter Augusta’s lush green fairways, while red and brown hues colour the towering pine trees and dogwoods that surround the course.

But a few things are amiss.

The first being the pink azaleas that surround the greens like a blushed coral reef. Blooming only in the spring and summer months, the flower beds are significantly less vibrant this year.

And so too is the atmosphere. With no fans allowed entry to the grounds, this year’s tournament will lack the electricity of the patrons.

“It’s going to make a big difference to all of us,” said 2019 champion Tiger Woods.

“At Augusta, you just have all those roars that would go up if somebody did something, somewhere, and look to the scoreboard watching, trying to figure out what’s going on.”

As well as the aesthetics, the course will be playing a lot different from what we’re used to. With temperatures dropping by 10ºc and northerly winds coming in to hit players on the nose as they tee off on the first hole.

That’ll mean the ball will carry a lot less this week.

Everyone is also talking about how much softer the course is playing compared to normal. After a combination of autumnal rainfall and heavy watering following Georgia’s hot summer, the course is playing a lot longer than it would in April.

“It’s going to be so much longer and wetter,” said Tour Pro Kevin Kisner.

“Every year in November I hit 4-iron into No.1 because it plays into the wind and there’s no roll. And when it’s colder in November than in April, the ball doesn’t go as far. So if I hit it 285 in April, I hit it 270 in November.”

“You’re going to have to hit a lot of long irons into greens.”

With the course being so soft, those who can strike the ball further will take the advantage, which is slightly ironic considering the distance debate that has been brewing over the past couple of months following Bryson DeChambeau’s emphatic win at the US Open.

A Divided Camp

You could say a civil war in golf has emerged.

DeChambeau sits in one corner with his 48-inch driver facing off against many traditionalists of the game and the governing bodies of golf.

Focused solely on breaking the barrier of what was once thought physically possible with a golf club, DeChambeau is proving his doubters wrong, winning tournaments by teeing it high and letting it fly.

Averaging 322 yards with his driver on the PGA Tour last season, DeChambeau has transformed himself to go one step further this year and break the 400-yard barrier.

He certainly got close at this year’s U.S. Open, driving the ball 375 yards on the 9th hole at Winged Foot during his final round.

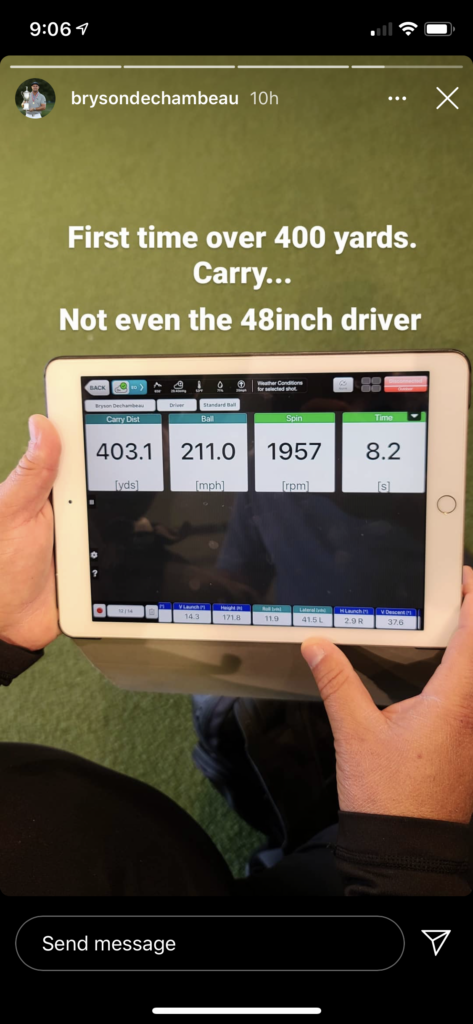

But he’s proved the feat is possible after posting a story on his Instagram showing that he’d carried a shot 403 yards with a ball speed of 211mph with his driver on the range.

Impressive stuff. But it hasn’t come without hard work. DeChambeau has committed himself to training over the past year, to bulk up and get stronger to achieve these incredible distances.

“I saw him in May; he’s done all the work to get stronger. He said he’d had a bad back and it took him a year to get his back strong. He studies the science of this game and one of the sciences is physical,” 3-time Masters champion Nick Faldo said to the BBC.

He’s also been optimising his equipment, trialling a new 48-inch driver, the longest shaft players are legally allowed to have in their bag and is planning to unleash it on the Masters.

DeChambeau is certainly pushing the limits of the game of golf much to the criticism of many within the sport.

Matt Fitzpatrick was one of his most notable critiques, claiming after the U.S. Open that “it is not a skill to hit the ball a long way.”

“I drove it brilliantly, and I actually played pretty well, and I’m miles behind… it just makes a bit of a mockery of it I think… It doesn’t matter if I play my best, he’s going to be 50 yards in front of me off the tee,” Fitzpatrick said.

“The skill, in my opinion, is to hit the ball straight. That’s the skill. He’s just taking the skill out of it.”

Fitzpatrick has a point that in some ways, golf’s bigger hitters are turning the game into a slogging match.

But Fitzpatrick, for me, is also wrong.

Simply put, the real skill in golf is not how far or how straight can you hit the ball, it’s how few shots you can score on each hole.

Scoring low rounds requires a golfer to be a perfectionist in every part of their game. From driving to putting, there are shots to be won all around the course, so the real skill in golf is how you get around with the lowest score.

It is a little depressing when you do see players whacking the ball 400 yards, eliminating the hazards and trepidations of some of the hardest courses in the world.

And before we get into the arguments of whether the Tours should be nerfing equipment or making courses longer, let’s look at the numbers from the U.S. Open.

Although Bryson DeChambeau was the longest hitter on the PGA Tour this year, he came 7th at Winged Foot for the longest average drive, with Dustin Johnson and Matt Wolff being the biggest hitters.

More notably, DeChambeau was second for shots gained around the greens behind Xander Shauffelle and 3rd for approaches.

Going into the final round, DeChambeau upped his putting game too, syncing a 30-foot putt to hole out for an eagle on the 9th.

In 2017 the American was ranked 145th on the PGA Tour for shots saved from putts. Fast forward to 2020 and Dechambeau has vastly improved his work on the greens, climbing the ranks to become the 10th best player on the PGA tour for shots saved from putts.

Put it this way, it wasn’t just the long shots that got Bryson the win at Winged Foot.

The Future Of Golf

With several players on the verge of outdriving the golf course, 2014 Ryder Cup Captain Paul McGinley has voiced his concerns over the future of the game, calling on golf’s governing bodies to “step up to the plate.”

McGinley claimed DeChambeau’s U.S. Open triumph “was not a tipping point but it highlighted what’s happened in the last decade and that big-hitting is absolutely dominating the top of the game.”

Siding with Fitzpatrick he stated, “if you’re not a big hitter, you have got little or no chance of competing at the top level.”

Perhaps he’s right, golf’s shorter hitters will be left behind.

It’s no good extending golf courses; real estate is an expensive and sparse luxury these days, and that will just encourage tour pros to hit it even further.

One of the only real options officials have is to nerf the equipment the pros use.

But perhaps it’s too little too late, with the USGA and R&A being too slow to react as DeChambeau isn’t the first to try this, and in some ways, it’s unfair for him to be taking all this flack.

Golfers have been pushing at the boundaries of how far they can carry the ball for nearly twenty years now.

Butch Harmon recalled the similarities between DeChambeau and Tiger Woods in the 1990s stating, “when Tiger first came to Augusta, he was doing the same things that Bryson is doing now.”

“He was hitting short irons into the par-fives and the powers at Augusta didn’t like it when the media said they ‘Tiger-proofed’ the golf course because they didn’t like how far he was hitting it.”

And he’s right, this has been going on in golf for some time now, with DeChambeau not being the only player to try to out drive the course.

“Guys are figuring out how to carry the ball 320-plus yards, and it’s not just a few of them,” Tiger Woods said in an interview last week. “There’s a lot of guys who can do it. That’s where the game’s going.”

U.S. Open champion Graeme McDowell summarised the situation well in an interview with the BBC, siding with Woods that players like Bubba Watson and Brooks Koepka have been able to hit the ball over the trees on the 13th hole at Augusta and “make a mockery of the hole” for some time now.

“I guess that’s where the debate goes when the integrity of some of the greatest holes in the world starts to be challenged,” McDowell affirmed.